The story of one of the greatest scandals in French history, the Affaire du Collier de la Reine, which irrevocably contributed to the downfall of the monarchy under Louis XVI. At the heart of this fascinating intrigue, a priceless diamond necklace commissioned by Louis XV from the jewelers Boehmer and Bassange, and originally intended for Madame Du Barry, finds itself at the center of an extraordinary legal affair that unjustly tarnished the reputation of Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette.

Historical context

In 1772, Louis XV wished to make a gift to his favorite Madame du Barry. He asked two German jewelers, Charles Auguste Bohemer and his associate Paul Bassanges, commonly known as the Bohemers, to create a diamond necklace of unparalleled richness.

Renowned Parisian merchants, Bohemer and Bassanges were established in Place Louis-le-Grand. Formerly jewelers to the Polish court, they counted the French court and numerous foreign sovereigns among their clients.

Confident of their success, they single-handedly financed the manufacture of the necklace, incurring considerable debt. The project took a long time, due to the difficulty of gathering diamonds of the desired purity. Unfortunately for them, Louis XV died in 1774 and Madame du Barry was exiled.

The necklace was finally completed in 1778.

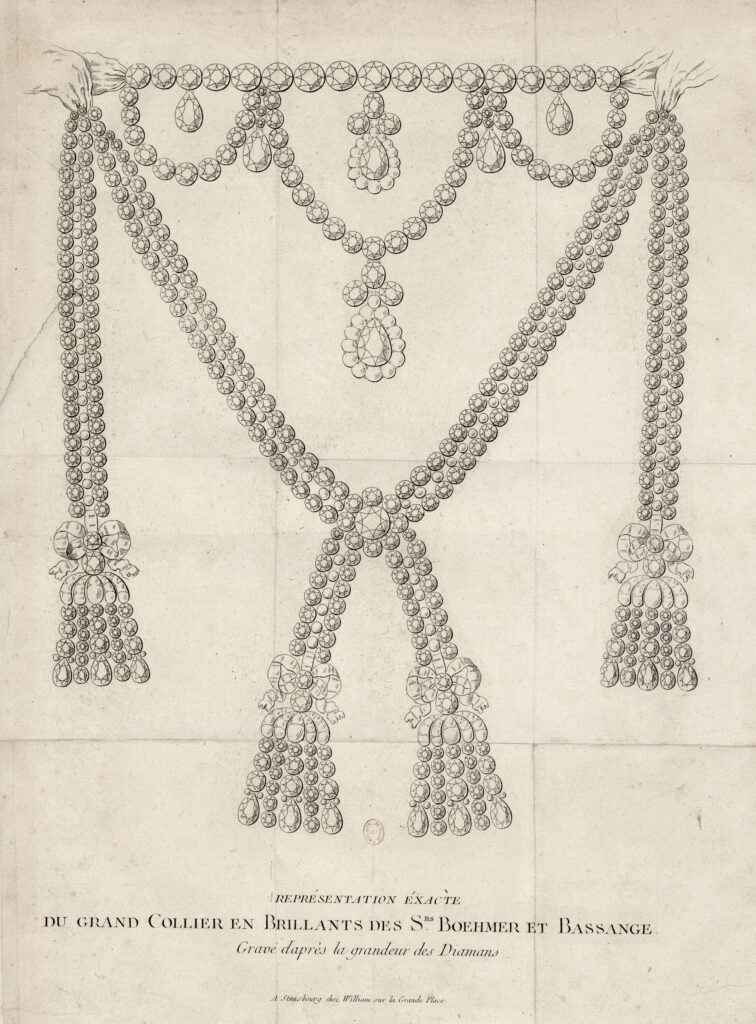

A true masterpiece, this “Grand collier en brillants”, as it is officially known, adopts an elaborate “en esclavage” composition. A row of 17 diamonds, ranging in size from 5 to 8 carats, forms a three-quarter neckline that is fastened at the back with silk bands. It supports three garlands adorned with 6 pendants set with pear-cut diamonds in an entourage of fine pearls.

On the sides, two long ribbons of two rows of diamonds and one row of pearls pass over the shoulders and fall down the back. The two middle ribbons cross over a 12-carat diamond surrounded by pearls at the bosom. The ribbons end in diamond bangs topped with enameled bows.

The jewel features a hundred pearls and 674 diamonds of exceptional purity, for a total of 2840 carats.

When the reign of Louis XVI began in 1774, the economic situation was disastrous, with expenditure exceeding revenue by 22 million. As a result of interest on loans and unjustified expenditure, the State owed 235 million immediately due. In all, the monarchy’s coffers were short 335 million.

On the verge of bankruptcy and desperate, it was against this backdrop that the two jewelers insisted on offering the necklace to Marie-Antoinette for the colossal sum of 1,600,000 livres (approximately €27,513,000). The queen’s taste for gems was notorious, and earned her the reprimands of her mother, Empress Marie-Thérèse.

Louis XVI, himself an excellent connoisseur, wanted to give her the necklace, but Marie-Antoinette refused. According to Madame Campan, she said the money would be better spent on building a ship at a time when France had just allied itself with the American insurgents. She added that the necklace would be of little use to her, as she now wears diamond ornaments only four or five times a year.

Finally, the heavy necklace, which resembled those of the previous reign, was not to Marie-Antoinette’s taste, as she compared it to a “horse harness”.

After trying to sell their necklace to the European courts of Spain, England, the Two Sicilies, Tuscany and Russia, the jewelers tried once again to sell it to Marie-Antoinette after the birth of the dauphin Louis-Joseph in 1781. Louis XVI was close to agreeing, but the defeat at Les Saintes once again put paid to the project.

The following year, Böhmer threw himself at the Queen’s feet, threatening to take his own life. Marie-Antoinette refused one last time to buy the necklace, and advised him to loosen the diamonds so as to sell the most important ones at a good price. She retorted: “Don’t ever talk to me about it. Sell it and don’t drown!

The protagonists

Cardinal Louis-René-Édouard Prince de Rohan

Louis-René-Edouard de Rohan became a canon in the bishopric of Strasbourg at the age of 9. At 26, he was consecrated bishop, then prince-bishop a year later. A poet and philosopher, he was elected to the Académie Française in 1761 at the age of 27. But the cardinal had a few vices: he loved money and women.

Cardinal de Rohan was appointed French ambassador to Vienna and led a debauched life, spending lavishly and flaunting his many mistresses. He had spied on the correspondence between Marie-Antoinette and her mother, Empress Maria Theresa, which earned him the hatred of the new Queen of France.

After his recall from Vienna, the cardinal fell out of favor with Queen Marie-Antoinette, and on the advice of her mother, Maria Theresa of Austria, she dismissed him from her circle for his licentious morals. Anxious to regain her trust, the cardinal was prepared to do anything.

In 1777, however, Prince Louis de Rohan was appointed Grand Chaplain. The grand aumônier had a symbolic role as the most important ecclesiastic of the court: the grand aumônier gave communion to the king, and celebrated the princes’ baptisms and marriages.

Despite Marie-Antoinette’s fierce opposition, he became abbot of the wealthy abbey of Saint-Waast near Arras, then ordained cardinal, thanks to the intervention of the King of Poland.

The cardinal did not, however, renounce his former life, and it was under this new title that he met our second protagonist: Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy.

Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, Countess de La Motte

Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, a distant descendant of a bastard son of King Henri II, is also known as Countess de La Motte through her marriage to Nicolas de La Motte, and as Countess de La Motte-Valois through usurpation of her noble title.

The marriage between Jeanne and her husband was a failure, but they continued to live together. Jeanne took a lover, Louis Marc Antoine Rétaux de Villette, a gigolo.

Her husband soon proved unable to support the couple, so the countess decided to use her ancestry to gain financial advantage. A frequent visitor to the Château de Versailles, where anyone in decent clothes could enter, she repeatedly tried to introduce herself to Queen Marie-Antoinette. Queen Marie-Antoinette, warned of her dubious reputation, would never accept.

Around 1783, Jeanne’s protector, Madame de Boulainvilliers, introduced her to the bishop of Strasbourg, Cardinal de Rohan, and she became his mistress. She had spread the word that she had the Queen’s favor, and succeeded in restoring hope to the Cardinal, who was seeking to regain Marie-Antoinette’s confidence.

Louis Marc Antoine Rétaux de Villette

Louis Marc Antoine Rétaux de Villette was born in Lyon in 1754, the last son of a family of minor nobility that lacked the financial means to establish him at the height of his social standing.

He was found in Paris around 1778, at the age of 19, under the identity of “Comte de Villette”, a title he usurped from his older brother. He made his living as a pimp, recruiting young women and entrusting them to the owners of a brothel, who paid him in return. It is thought that he must also prostitute himself to get by financially. It was during this period that Villette developed a talent for forgery, forging bills of exchange and blackmailing his customers.

The beginnings of the affair

The two jewelers, unable to sell their necklace, were desperate. At the time, there were very few personalities capable of offering them the sum requested.

The story of this extraordinary necklace broke at the Château de Versailles and reached the ears of the Comtesse de La Motte-Valois, then lover of the Cardinal de Rohan and the Comte de Villette, always on the lookout for a way to enrich herself and rise socially.

The Countess had already set up a scheme with her second lover to extort money from Cardinal de Rohan.

She had led the cardinal to believe that she had become an intimate of the Queen. The disgraced Cardinal was desperate to regain her favor.

The Countess de La Motte gave the Cardinal hope of a return to favor with the Sovereign. In desperate need of money, she began by extracting 60,000 livres from him on behalf of the queen, which he granted her, while the countess provided him with forged letters of gratitude from the queen, announcing the hoped-for reconciliation, while postponing indefinitely the successive appointments requested by the cardinal to secure it.

Behind these forged letters was Louis Marc Antoine Rétaux de Villette, whose forging skills enabled him to imitate the queen’s handwriting perfectly. For his mistress, he forged letters signed “Marie-Antoinette de France” (although the queen signed only Marie-Antoinette, as the queens of France signed only by their first names).

The demands for money begin to worry the Cardinal de Rohan, who becomes very insistent and asks his lover to arrange a meeting with the Queen.

The Countess finds herself in a very delicate position, and her deception is in danger of being exposed. But then a miracle happens.

Her official husband, the Comte de la Motte, had discovered that a prostitute called Nicole Leguay had built up a reputation for herself because of her resemblance to Marie-Antoinette. The Comtesse de La Motte receives her and convinces her, in exchange for 15,000 livres, to play the role of the Queen at an organized rendezvous.

On the night of August 11, 1784, the cardinal received confirmation of a rendezvous at the bosquet de Vénus in the Versailles gardens at eleven o’clock in the evening.

There, Nicole Leguay, disguised as Marie-Antoinette in a polka-dot muslin dress, her face wrapped in light black gauze, greeted him with a rose and whispered, “You know what this means. You can count on the past being forgotten”.

Before the Cardinal can continue the conversation, the Countess de La Motte appears with Rétaux de Villette warning that the Countesses de Provence and d’Artois, the Queen’s sisters-in-law, are approaching.

This invented setback shortened the meeting. The next day, the cardinal received a forged letter from the “queen”, regretting the brevity of the meeting. The Cardinal is definitely won over, his gratitude and blind trust in the Countess de La Motte unshakeable.

Then the story of the sumptuous necklace refused by Marie Antoinette reached the ears of the Countess. Playing on the queen’s reputation for a passion for jewels, she set out to pull off the coup of a lifetime, this time swindling the cardinal out of 1.6 million livres.

How the case unfolded

On December 28, 1784, still presenting herself as an intimate friend of the Queen, Mme de La Motte met the jewelers Boehmer and Bassenge, who showed her the 2,840-carat diamond necklace they wished to sell by any means possible.

She tells the jewelers that she will intervene to convince the Queen to buy the jewel, but through a nominee.

In fact, in January 1785, Cardinal de Rohan received a new letter, again signed “Marie-Antoinette de France”, in which the Queen explained that she couldn’t afford to buy the jewel openly, and asked him to act as a go-between, contracting to repay her in four instalments of 400,000 livres.

The cardinal then sought advice from his lover, who assured him that if he accepted, the queen’s gratitude would know no bounds, favors would rain down on the cardinal’s head, and the queen would have the king appoint him prime minister.

On February 1, 1785, convinced, the cardinal signed the four drafts and had the jewel delivered, which he took that very evening to Mme de La Motte in an apartment she had rented in Versailles. In front of him, she passes it on to an alleged footman in the Queen’s livery (none other than Rétaux de Villette). Mme de la Motte even receives some very nice gifts from the jeweller for facilitating this negotiation.

Selling the necklace

Immediately, the crooks clumsily loosen the necklace with a knife. Jeanne commissioned Rétaux de Villette to sell fragments of the necklace, but he soon ran into trouble. The diamonds were of exceptional quality and weight, and de Villette’s asking price was derisory compared to the real value, which immediately caught the attention of the various diamond dealers. He is arrested with his pockets full of diamonds.

Some time after his visit to the various merchants, a jeweler named Atlan had come to the police inspector for the Montmartre district, Brugnières, to tell him that a man named Retaux de Villette was peddling brilliants to merchants and Jews, offering them at such low prices that no one wanted to buy them, suspecting theft.

Brugnières raided Retaux de Villette’s fifth-floor apartment on rue Saint-Louis in the Marais district. He forced him to make a statement to the local superintendent. Confused and hesitant, Retaux finally confessed that he had the diamonds in his possession from a lady of quality, a relative of the King, named the Comtesse de Valois La Motte.

The latter realized that selling the diamonds in Paris was a folly and asked her husband to dispose of most of the necklace in England, while she insisted that Rétaux sell the brilliants in Holland.

The Comte de La Motte left for London, presenting the diamonds as coming from a belt buckle that had long been in his family, an old-fashioned piece of jewelry he wished to part with. To cover his tracks and avoid detection, he decided to adopt a different strategy, preferring to exchange the diamonds for objects or have them reassembled as jewels for resale.

He contacted London’s leading jewelers, Robert and William Gray, partners in New Bond Street, and Nathaniel Jefferys, a jeweler in Piccadilly.

The Earl presented himself with his hands full of the most expensive brilliants. Some, said the jewellers, were damaged, as if torn from an ornament, by a hasty and clumsy hand, with a knife. They were the diamonds in the necklace. The jewellers later recognized them from the drawings sent to them by Bohemer and Bassanges.

However, La Motte offered them so far below their value that, in turn, the English jewelers suspected larceny. They had the French embassy make enquiries, but as there was still no mention of any diamonds being stolen, they agreed to negotiate, and bought from La Motte brilliants worth over two hundred and forty thousand pounds; others, amounting to a value of sixty thousand pounds, were left by the count in their hands to be mounted as jewels of various kinds; others, representing a sum of eight thousand pounds sterling, were hastily exchanged for the most diverse objects, of which we have a list: an assortment of watches with their chains, ruby earrings, miniature snuffboxes, pearl necklaces, earrings and a brilliant ring.

Most of the Collier was sold, exchanged or left in the hands of jewelers Gray and Jefferys.

Mme de la Motte sold diamonds in Paris to a jeweller for 36,000 livres.

And despite all the diamonds strewn about, Régnier still sees a jewel case of brilliants in her home, which he estimates at least at 100,000 livres, while the Comte de la Motte keeps 30,000 livres in his pocket.

Jeanne also prepared for her husband’s return and his impressive change of lifestyle by announcing to everyone that her husband had returned from England after making substantial gains at the races.

He returns from London with horses, liveries, carriages, furniture, bronzes, marbles, crystals, dazzling luxury. The couple returned to settle in Bar sur Aube, which they decided to furnish with pomp, tapestries, furniture, bronzes and crystal chandeliers. The La Motte couple even had six carriages and twelve horses.

The Count and Countess threw party after party, reception after reception. They kept an open table. The luxury of the house was such that the locals had never seen anything like it. But they had all known the misery of Nicolas de la Motte and Jeanne de Valois.

The outcome of the case

In the meantime, the jeweler and the cardinal have set the first deadline for August 1. However, the craftsman and the prelate are astonished that the Queen is not wearing the necklace in the meantime. Mme de La Motte assures them that a great opportunity has not yet arisen and that, until then, if they are asked about the necklace, they must reply that it has been sold to the Sultan of Constantinople.

In July, however, with the first deadline approaching, the time had come for the Countess to buy time. She asked the cardinal to find lenders to help the queen repay the debt. Indeed, she would have trouble finding the 400,000 livres she owed by this deadline.

But it was the two jewelers who were to precipitate the outcome. Having learned of the payment difficulties ahead, they went straight to Marie-Antoinette’s first chambermaid, Mme Campan, and discussed the matter with her.

The latter was stunned and, naturally, immediately reported her conversation with Boehmer to the Queen. Marie-Antoinette, for whom the affair is incomprehensible, instructs Baron de Breteuil, Minister of the King’s Household, to clear things up. Baron de Breteuil was an enemy of Cardinal de Rohan, having coveted his position as ambassador to Vienna, but to no avail. Discovering the swindle in which the Cardinal is involved, he intends to give it all the publicity he can to harm him.

The Countess, sensing the suspicions, has meanwhile arranged for the Cardinal to receive an initial payment of 35,000 livres, thanks to the 300,000 livres she received from the sale of the necklace, which she has already used to buy a country house.

But this payment, which was derisory, was now useless. At the same time, the Countess informs the jewelers that the Queen’s alleged signature is a forgery, in order to scare Cardinal de Rohan into paying the bill himself for fear of scandal.

The king was informed of the swindle on August 14, 1785. On August 15, just as the Cardinal – who was also Grand Chaplain of France – was about to celebrate the Assumption mass in the chapel of the Château de Versailles, he was summoned to the King’s apartments in the presence of the Queen, the Miromesnil Keeper of the Seals and the Minister of the King’s Household, Breteuil.

He is summoned to explain the case against him. The prelate realizes that he has been fooled all along by the Countess de La Motte. At first, he can’t explain. The king lends him his office to prepare his defense and arguments. Meanwhile, Marie-Antoinette, very angry and impulsive, with no thought for the consequences, asks Louis XVI to send Cardinal de Rohan to the Bastille that very evening. Rohan returned with his “writing”, and began to be questioned by the king. “Do you have the necklace?” he asks. Stunned, Rohan answers no, looking at the Queen, who turns away disdainfully. The Queen adds: “And how could you think that I, who have not spoken to you in ten years, would address you on a matter of this nature?

The cardinal tries to explain. “My cousin, I warn you that you are going to be arrested,” the king tells him. The cardinal begs the king to spare him this humiliation, invoking the dignity of the Church, the name of the Rohans, the memory of his cousin the Countess de Marsan who raised Louis XVI. The king hesitates, but faced with the pressure of Marie-Antoinette at his side, the king turns to him: “I’m doing what I must, as king, and as husband. Leave”. As he left the king’s apartments, he was arrested in the Hall of Mirrors, amidst the astonished courtiers.

With the Court in shock, he asks a clergyman if he has paper and pencil, then goes to his Grand Vicar to hand him this hastily-written missive, so that he can burn any letters Marie-Antoinette may have sent him. The court was scandalized by this extraordinary arrest, for the Rohan name is one of great nobility, but Marie-Antoinette was convinced she would be showered with praise. However, that very evening, faced with the coldness of the court towards her (and the embarrassment of her friends), she felt “confusedly” that she had just made a mistake that would cost her dearly.

The Cardinal is imprisoned in the Bastille. He immediately began repaying the sums owed, selling off his own property, including his château de Coupvray. Until 1881, the descendants of his heirs continued to repay the jeweler’s descendants.

The Comtesse de La Motte was arrested, and her husband fled to London, where he was granted asylum with the last of his diamonds, while Rétaux de Villette was already in Switzerland. Then it was Nicole Leguay’s turn to be arrested in Brussels with her lover, with whom she was pregnant.

The trial

On May 22, 1786, the public trial opened before 64 magistrates and the Grand Chamber of the Parliament.

Cardinal de Rohan chose Jean-Baptiste Target as his lawyer, whose resounding plea made him famous and led to his election, less than 3 years later, as a Paris deputy of the Third Estate.

On May 30, 1786, the French parliament handed down its verdict in the face of a raging press. The Cardinal was acquitted of both the fraud and the crime of lèse-majesté against the Queen.

The Comtesse de La Motte was sentenced to life imprisonment at the Salpêtrière, after being whipped and branded.

Her husband was sentenced to the galleys for life in absentia, and Rétaux de Villette was banished from the kingdom.

The Queen, now aware that her image had deteriorated in the eyes of public opinion, got the King to exile Cardinal de Rohan to the abbey of La Chaise-Dieu, after dismissing him as Grand Chaplain. It was reported in Paris that “the Parliament having purged him, the king sent him to the chair”. Only after three years, on March 17, 1788, did the king allow him to return to his diocese of Strasbourg.

Although Marie-Antoinette was not involved in the whole affair, public opinion did not want to believe in the queen’s innocence. Long accused of contributing to the kingdom’s budget deficit through her excessive spending, she was subjected to an unprecedented avalanche of criticism through pamphlets in which the “Austrian” (or “other bitch”) was offered diamonds as the price of her love affair with the cardinal.

Mme de la Motte, who had denied any involvement in the affair, acknowledging only that she was the Cardinal’s mistress, managed to escape from the Salpêtrière and published an account in London in which she recounted her affair with Marie-Antoinette, the latter’s complicity from the start of the affair right up to her intervention in the escape.

Conclusion

Through the discredit it cast on an already hostile Court and the strengthening of the Paris Parliament, this scandal was, for some, directly responsible for the outbreak of the French Revolution four years later and the downfall of royalty.

Goethe wrote: “These intrigues destroyed the royal dignity. The story of the necklace is therefore the immediate preface to the Revolution. It is its foundation…”.

As for the diamonds, it is not yet known what became of them; they have probably been reassembled in other pieces of jewelry such as this necklace, which will be offered for sale by Sotheby’s and dispersed around the world.